Inner Circle ADD

Kate Simon - The Rebel Music Interview

12/04/2023 by Steve Topple

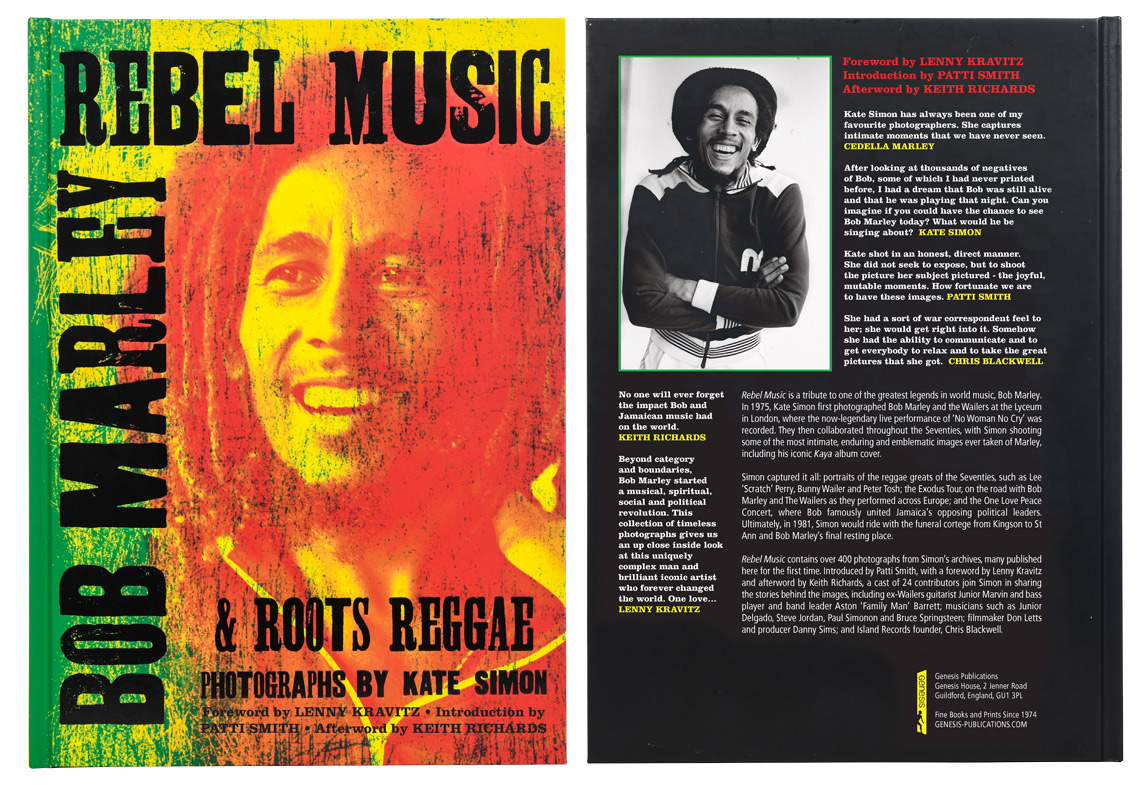

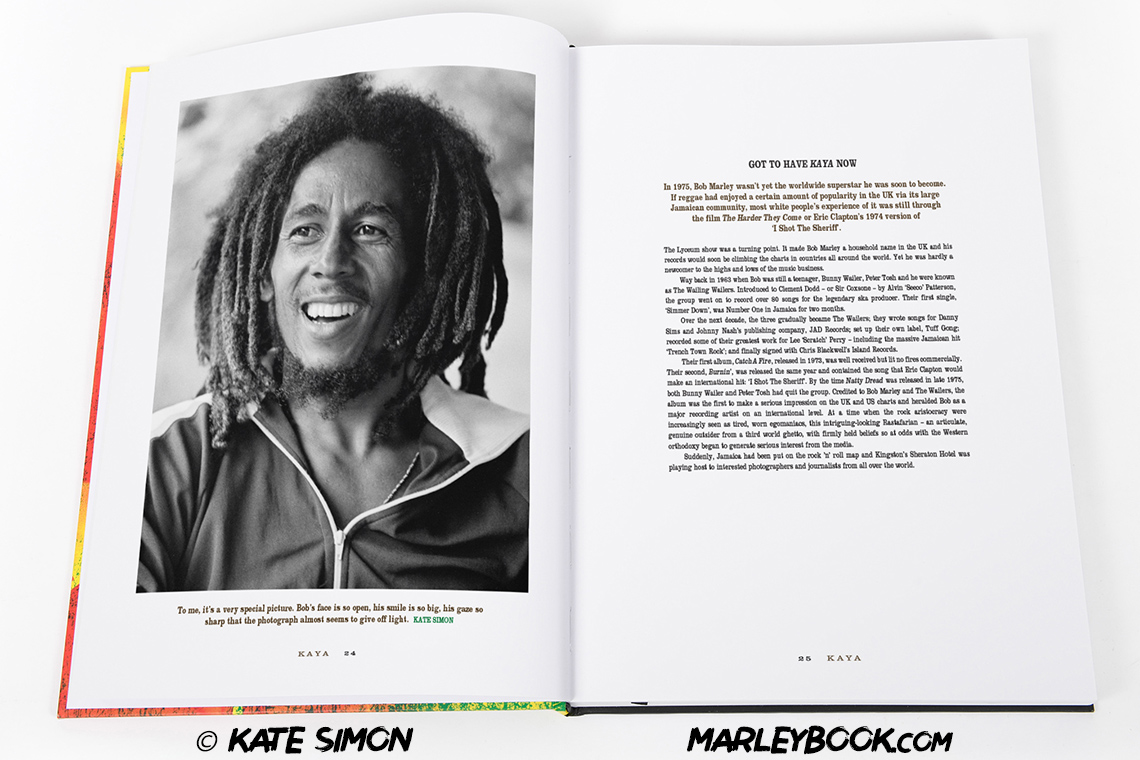

Kate Simon is perhaps one of the most well-known and iconic portrait photographers of the 20th century. She’s captured world-renowned images of global icons – from Madonna to Debbie Harry, via The Clash and Andy Warhol, and the Rolling Stones. However, Simon is perhaps best known for her photography of Bob Marley – not least the cover of his and the Wailers’ album Kaya.

Now, her groundbreaking collection of works, the book Rebel Music: Bob Marley and Roots Reggae, which is interspersed with quotes and comments from those around at this time in Jamaica’s history, has been re-released with some never-before seen images of Bob included.

So, Reggaeville caught up with Simon to discuss the book, her time with Bob and her experiences in Jamaica, and just what it was like to be around one of the most important musicians in history.

Thank you so much for joining us, Kate – it’s a real treat to have you here.

Thank you for having me – I really like Reggaeville!

Thank you – we try our best!

Well, it’s fantastic.

The reason we all do it is we have a passion for the music. It never feels like work.

You know, it’s funny – I was just in LA promoting Rebel Music. My photo assistant, because of our work together, he bought a Big Youth record. In other words, people like you and me aren’t necessarily the rule. It’s such an incredible genre of music, it’s so inventive – but it’s like being keen on Bee-Bop. I can’t imagine not knowing Reggae, and not knowing all the vagaries of the genre. So, I validate and understand your commitment!

[Laughs] Thank you! What I love about Reggae is the way it can lend itself to any other genre – where Reggae artists cover tracks, for example. I’m a trained classical musician, not really a journalist – so for me, there’s something about it which makes it special.

Well, we can be quite specific. When you’ve got a drummer like Carlton Barrett – he was an incredible drummer. And his brother Aston, when you have musicians as inventive and brilliant as them – and then you drop on top Bob’s rhythm guitar, his vocals, lyrics, and songwriting - they were great musicians. Tyrone Downie – these musicians in Jamacia, there were so many gifted musicians. It was like the beginning of Jazz.

I came to Reggae through Jazz, actually. My dad was a semi-professional Jazz musician – so I naturally progressed into Soul and Hip Hop, and then on to Reggae.

That’s interesting – Chris Blackwell I believe worked with Miles Davies. We had this discussion down at Goldeneye. I’m a classically trained musician in flute. My mother was a classical pianist, my brother was too. But the rhythm of Reggae, it’s very infectious, it’s very musical. When I was first sent down there in 1976 – imagine – I met Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, Bob, Horsemouth, Inner Circle, Jacob Miller, Burning Spear, the Twinkle Brothers, the Gladiators, the Heptones, Big Youth, Augustus Pablo – I could go on. There were some great musicians - and great recording studios and record stores. It was like a dream to go and photograph them. It was the beginning of this whole genre of music and there were a lot of great, great musicians – it was great for me to shoot these people, and they were really intelligent.

You talk about your time in Jamacia exceptionally fondly – even though you’ve had a remarkable career photographing some of the 20th century’s most iconic people. Was your work around Reggae your most important period?

It was one of the highlights. Working with Bob was a spiritual experience. You have no way of knowing something you worked on, that you applied yourself to, how it would end up. I wasn’t the only one who photographed Bob, but we had a good connection, and good rapport – and for some reason they still rank for me as some of my favourite photographs. I photographed William S Burroughs for 20 years, and while it was different culturally, I really adored photographing him. I’m a portrait photographer, and there’s certain people you become really connected with, and they know how to be great subjects, and your relationship is completely about you taking their photographs. That’s what my relationship with Bob was about. It’s an interesting relationship.

I find the term “relationship” interesting in the context of your time with him and the book – because there’s some wonderful shots. On page 118-199 there’s image of Bob clutching his parka like a vulnerable child, and then on page 135, one of him asleep with his guitar. Was he happy for you to capture him at any time – and was that due to your relationship?

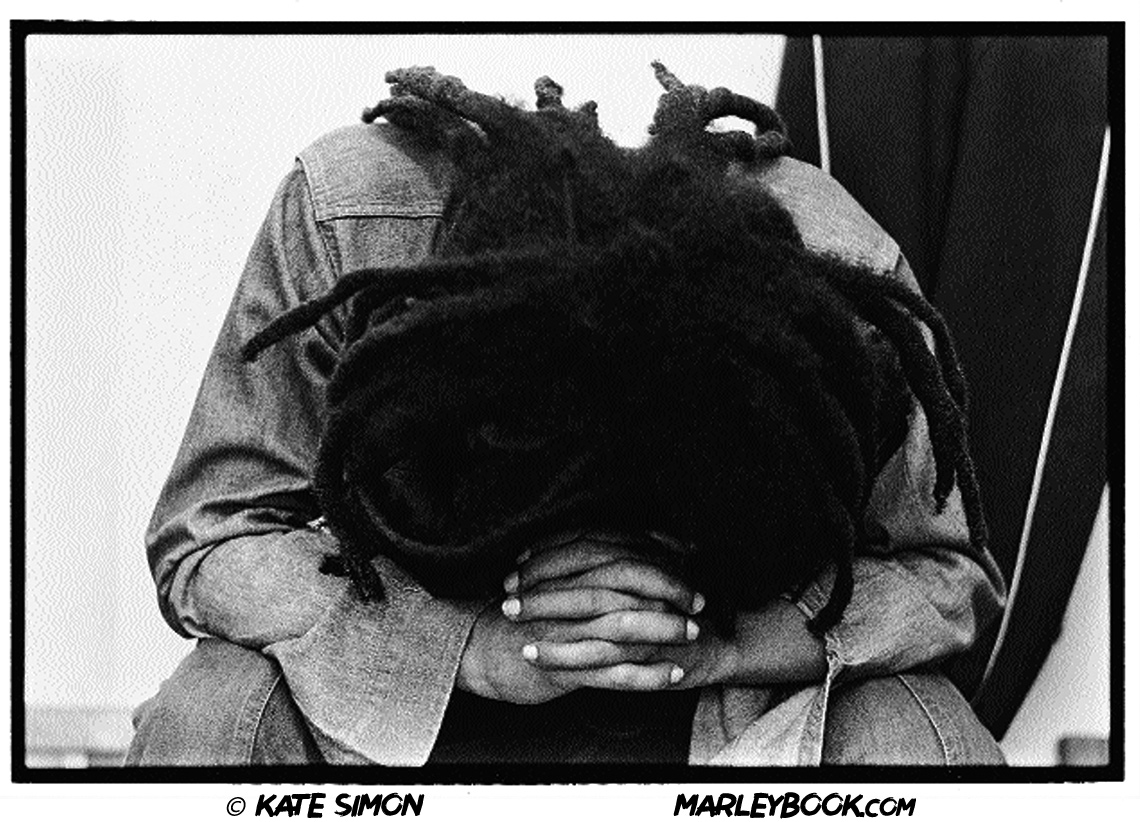

Yes, he was, and I would assume it was due to the relationship. That picture of Bob praying – he’d just done this incredible rendition of War – I’d never seen him do one like that before, it was so powerful. So, I went backstage right afterwards, and he was in the dressing room with his hands like he was praying. I don’t know if he was, but it looked like it.

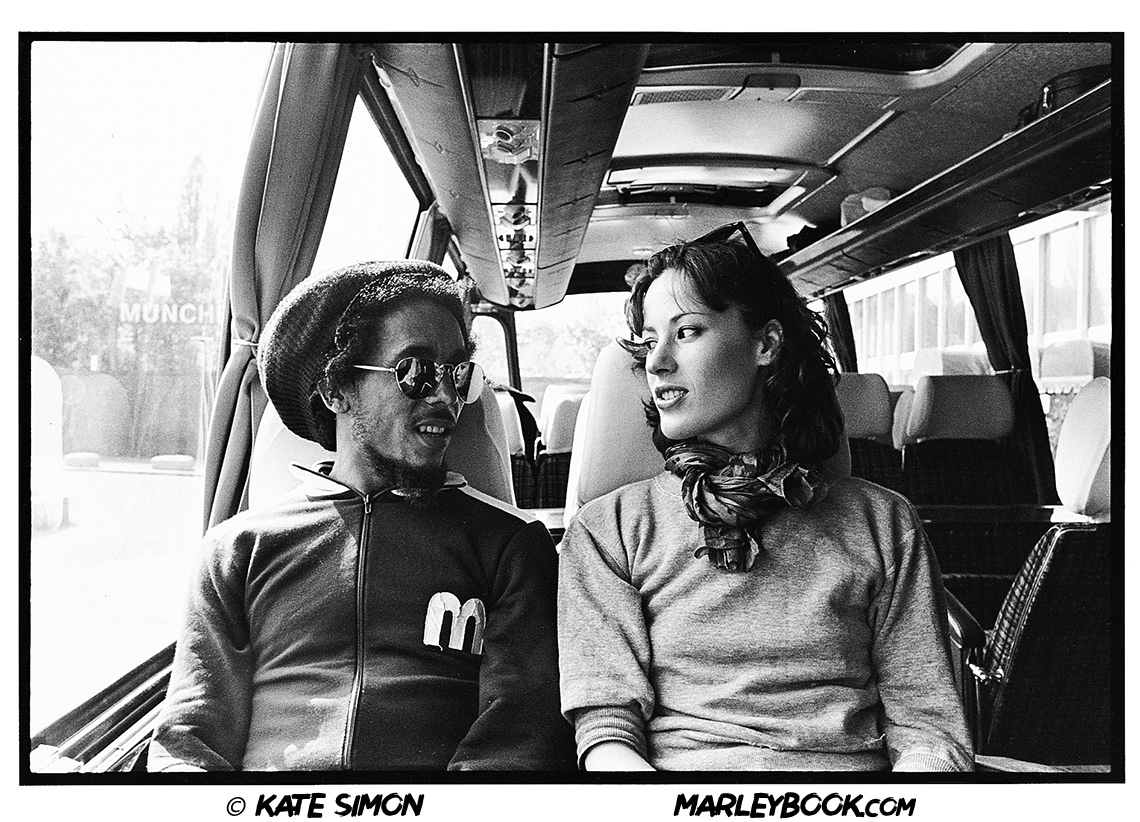

So, I knew, and I felt that – I was working as a photojournalist, my job was to photograph him – he was totally OK with me taking shots of him on the tour bus, or in sounds check, or during a live show, or when he was playing football or riding his bike. I would never invade his private space. Sometimes he’d be playing football in the hotel room, and there’d be Rita, Judy, and Gilly his cook who I’m still friends with, and that would be a photo opportunity. I’d only shot him when he was photo ready - but he knew how to be a great subject.

It’s fascinating to hear that because looking through the book, some of your images are so well know – like the Lyceum or Exodus shots – I’d argue hundreds of millions of people would know them. Yet some of the best shots are not the iconic ones. For example, the three-sequence shot on page 157 where Bob’s being interviewed by a journalist and he’s screwing his face, and which Steve Jordan has captioned “You’re asking the wrong questions” shows one of Marley’s most important character traits: that he spoke his own truth and would not deviate from that. Do you think that actually, some of the lesser-know shots are really the most captivating?

Thank you. I think that those ones where Steve Jordan has commented are great – Bob does look like ‘get me out of here’ [laughs]. In line with what you’re saying, there’s ones of Bob in Heidelberg at the artificial limb factory, and he’s looking at them – those are pretty unique, given how he had issues with his foot. Those are interesting. It’s interesting for me to hear you say these pictures are so well known – because a photographer can’t really know how well known their shots are. The Kaya shot – I assume that’s well known, but other than that I’m too inside it to know.

The Exodus ones, though – where he’s all in denim? My 17-year-old son would know those photographs, and I think most people would. But the thing with the least well know shots is that they show his humanity, you can feel and almost touch it.

My brother came for Thanksgiving and was looking at Rebel Music – and he pointed to the colour portrait of Bob wearing a white knitted cap. He said, ‘look at that, he’s really looking at you in a revealing way. It’s truthful’. And they are truthful. There’s no veil – they’re not showbiz pictures. They’re honest, real, with no filter.

Exactly. Overall, the book wasn’t what I was expecting, because there’s wonderful shots of other artists as well – like King Tubby with his crown on. That was delicious. And you also captured equally important images of everyday life in Jamaica in the 1970s.

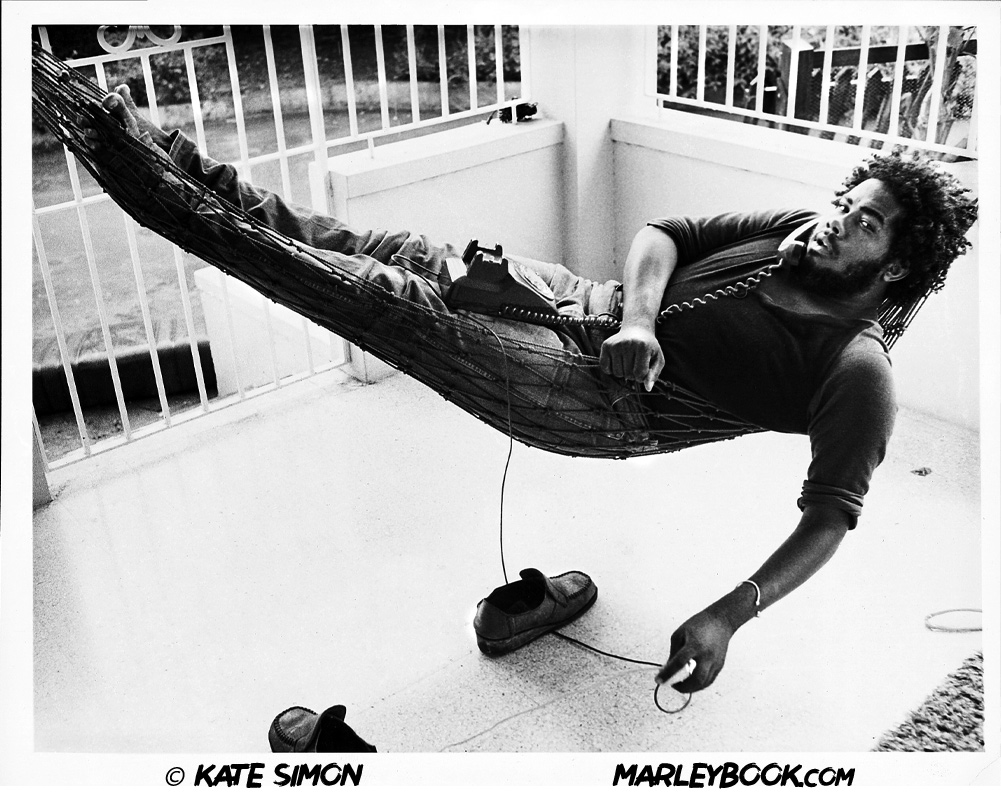

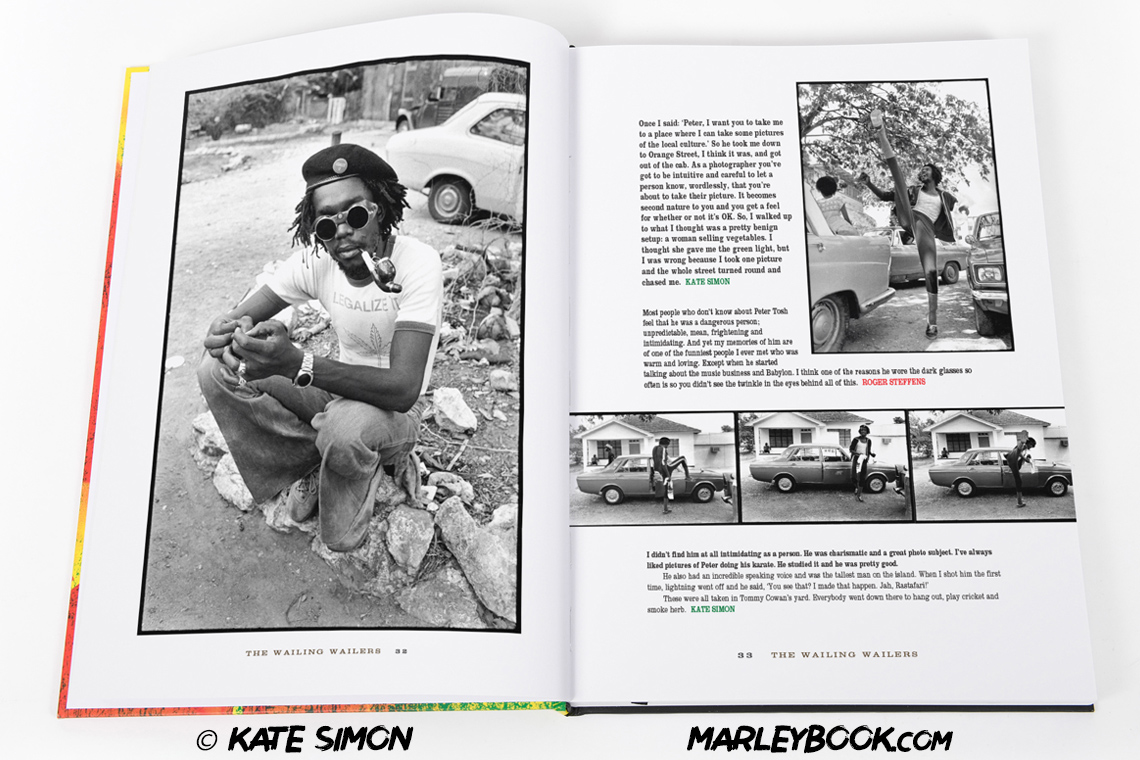

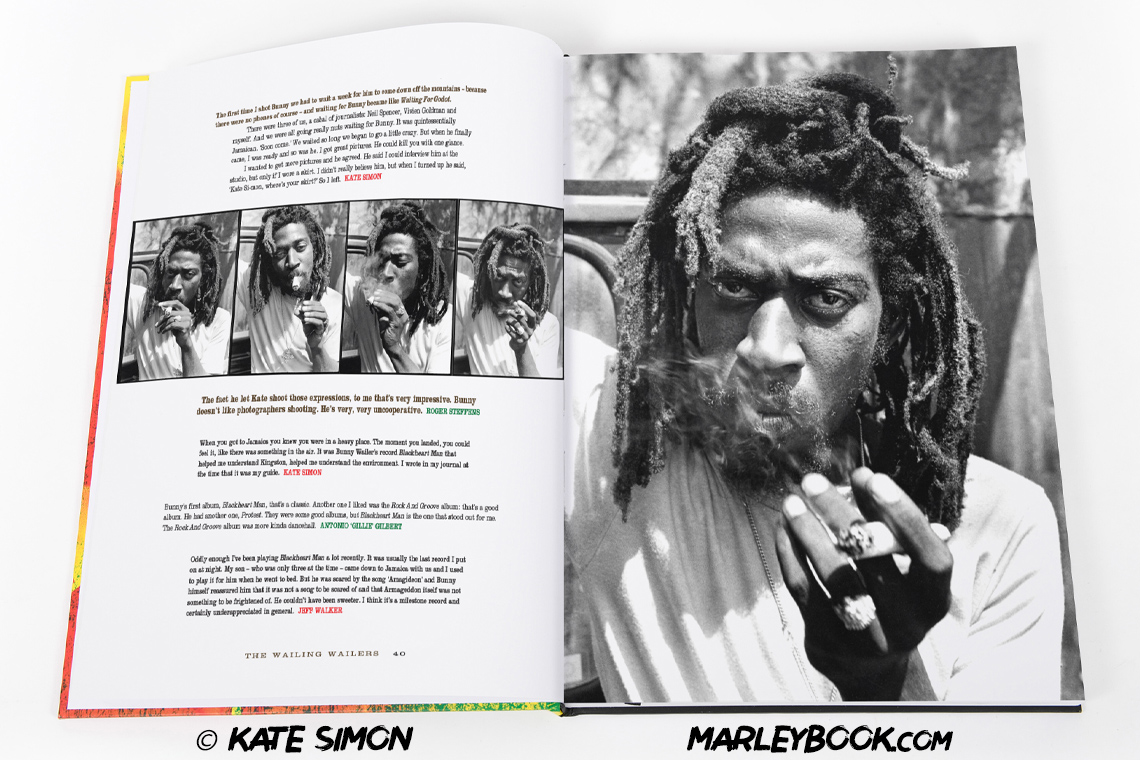

Well, I wanted the book to have Bob, and Bunny, and Peter – but also the street scenes to give a feel of Jamaica during the birth of Reggae. When I first went down to shoot Bunny for Blackheart Man, I wanted to show as much as I could of the culture – Jacob Miller in the hammock, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry in the studio. It was such a great opportunity. But the streets scenes – I said to Peter Tosh that I wanted to get some shots. So, he took me down to Orange Street, and I’m like, ‘OK bye – see you later’. I took a first shot of a woman selling vegetables and the whole street chased me down. I didn’t think there was anything wrong, but yeah!

Did that change your approach, or did you just carry on?

No, I just carried on – but I tried to be respectful. I photograph people, I’ve been doing it for a long time – so, you’ve got to know how people feel about the process, and that comes with application and years of experience. I think that was a one off, I never had any other problems. I respect people and their feelings about being photographed, and if they don’t want to be, I certainly won’t take their picture.

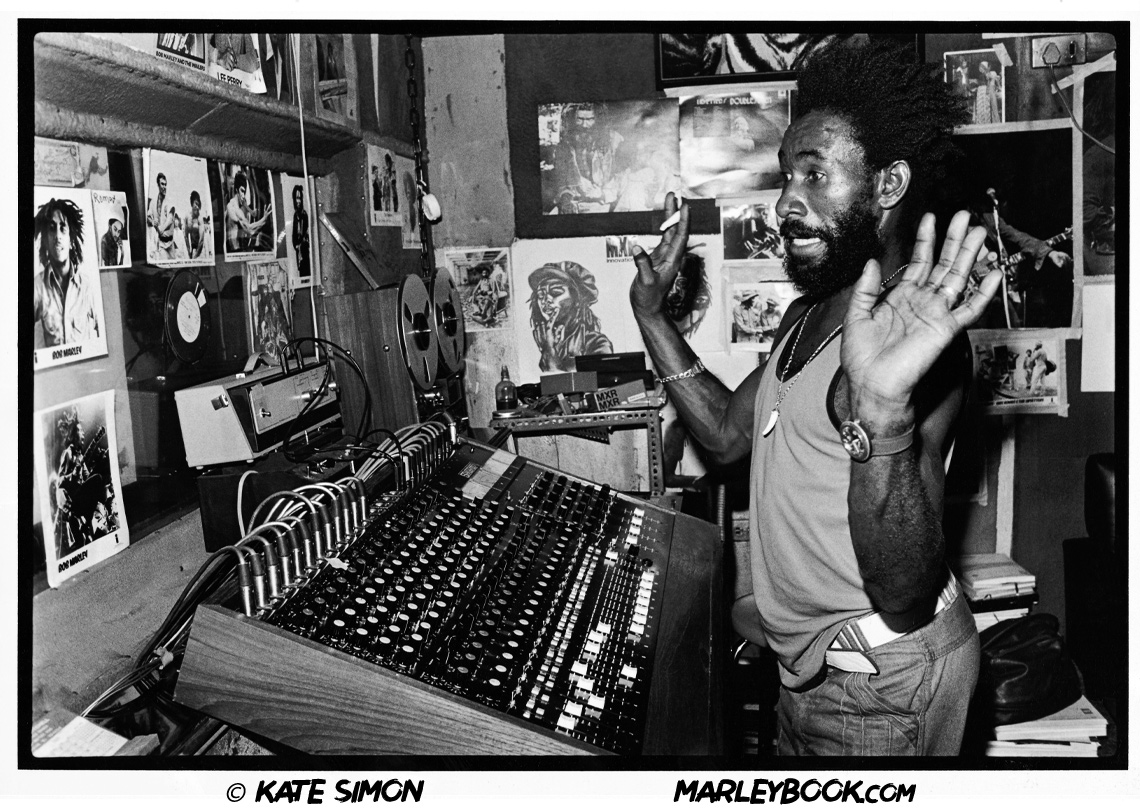

You mentioned Lee – there’s this brilliant shot of him on page 50 with his arms up in the studio like he was in shock [laughs], it’s just glorious. Having been around him, do you agree with David Kennedy that he was “eccentric”; Roger Steffens that he as a “little insane” – or was Lee something else?

I don’t think he was insane. I think that he was an incredible artist. I went back after I shot that in 1976, six months later, and he’d made huge painted murals out of some of my shots on the outside of the Black Ark Studio. He was an artistic creator with Bob, he worked with Robbie and Sly, and had a lot to do with creating the sounds of Dub. There’s was nothing crazy about a man who was working as hard as he was.

He was an artist. He wasn’t a straight! I don’t even think eccentric is applicable. When you’re cultivating a new language, and new way of expressing, a new way of reaching people – and when you’re one of the maestros of this new genre of music – this comes from an incredible gift, and incredible self-awareness; he was inspiring other musicians. So as opposed to being an eccentric who can be written off, we should see him as a mentor and a collaborator with some other gifted musicians who needed a little bit of his inspiration, his cheerleading, and his validation. He was so significant to the birth of Reggae.

A perfect way to describe him. Now, you touched on it earlier, but I’d like to expand on it: were you really not aware of the fact that your photographs are now historical documents of a few years of the birth of a movement and culture which has changed the face of music, but also how many people view the world? Did you really not know what you were documenting?

No, I didn’t. They say ‘youth is wasted on the young’ – and it’s not that I don’t enjoy who I photograph now, but this was something very special. I guess I must have been very inspired, or I wouldn’t have worked so hard, and the pictures wouldn’t have come out as well as they did. I was aware these individuals were really unique. I’d never seen anyone like Bunny, and to this day they’re some of the best portraits I’ve shot. This was incredible material, and I knew it was really special. I did realise at the time it was an incredible opportunity. I got back to London and put out these big spreads in NME and they looked like great photojournalism. And me, and a few other journalists, had a lot to do with introducing the UK to these very special musicians.

Well, it’s a fantastic book – not just the photography but the way its packaged with the quotes. You’re iconic in yourself.

Thank you so much. Well, I’ll have to put that out there!

[Laughs]. To wrap up, what was the personal highlight of your time with Bob?

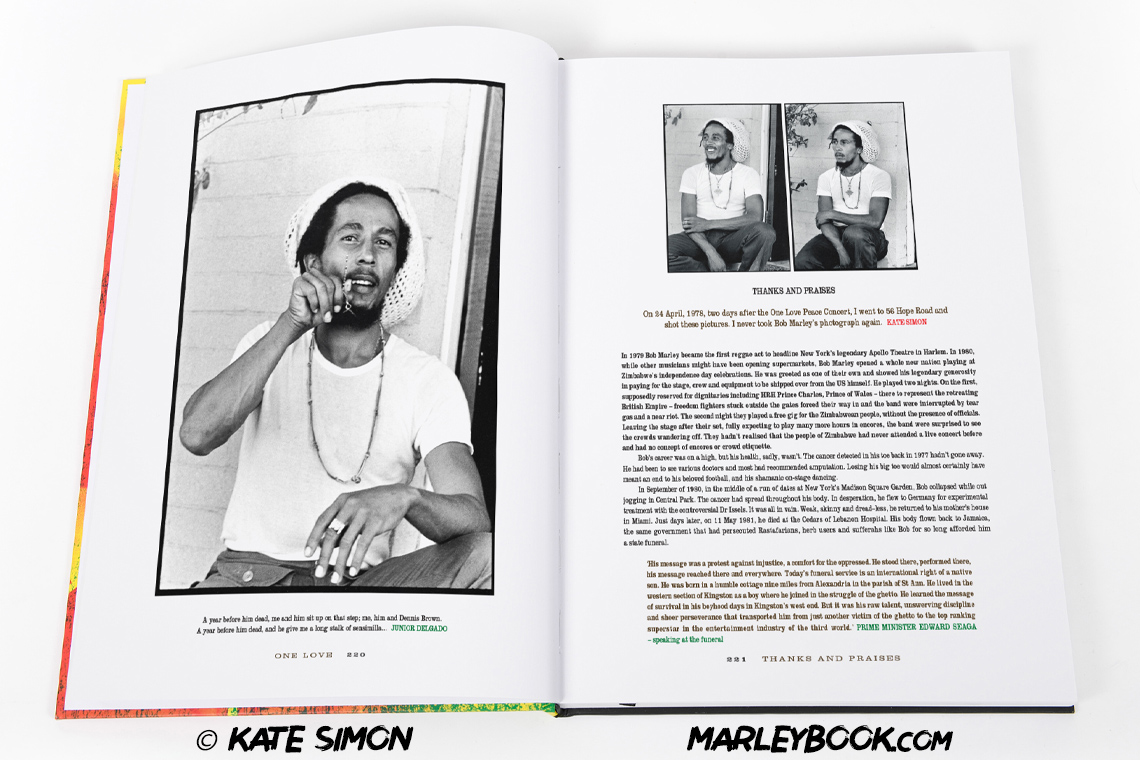

Well, I liked going to see him at the end of the Exodus tour at his house on Oakley Street in Chelsea, London. There’s this picture in the book where he’s wearing a sweatshirt, and he’s really relaxed. It’s like a moment where he’s saying, ‘I did it’. So, I like that picture because it reminds me of how we had worked together, and finished, and it was time to do London.

I like the memory I have of the last time I saw Bob. He was staying across the street from my studio, at Chris Blackwell’s apartment. I saw Bob right next to Carnegie Hall, he was crossing the street to go to a juice bar, and he shouted out to me ‘Kate Si-mon, what’s happening?’. That’s a great memory, but I wasn’t photographing him.

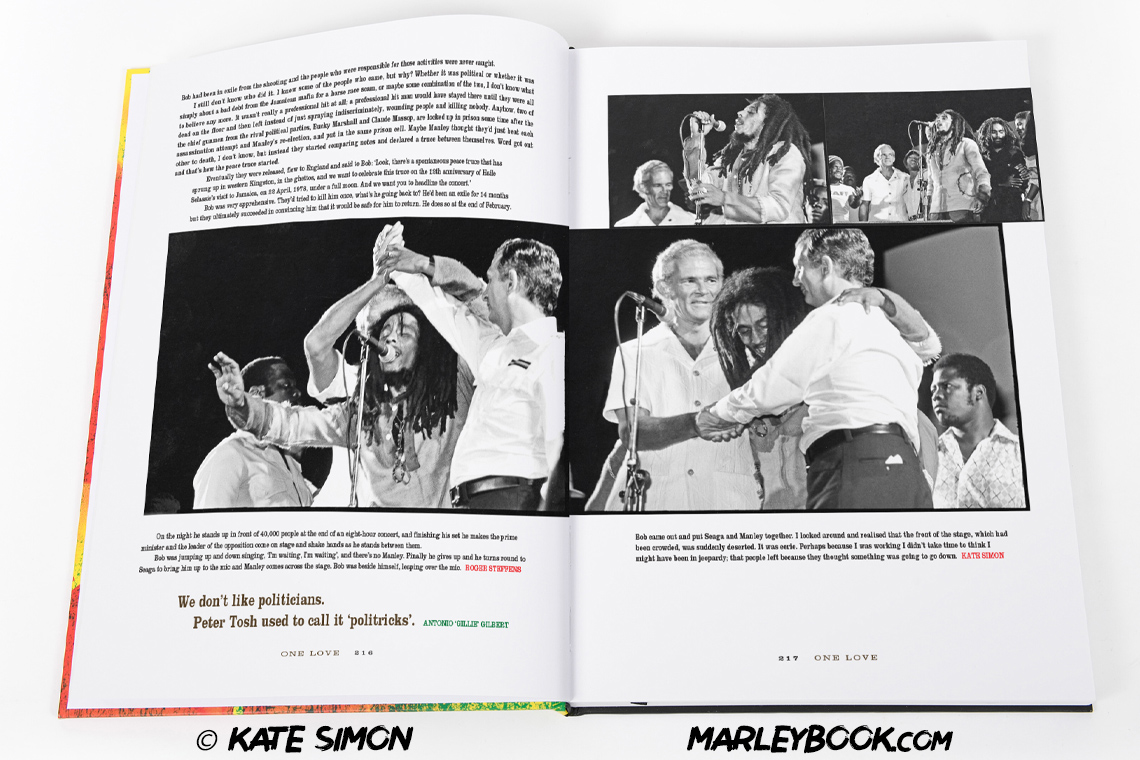

Also, photographing him in his house after the One Love Peace Concert is a really great memory. He’s holding up an Ethiopian cross. The look in his eyes is so clear, he’s looking joyful, like he’s saying ‘I did it. I achieved this unification of Manley and Seaga’. That’s what that picture says to me. So, those are the three.

Wonderful. Kate – thank you so much for talking to Reggaeville, it’s been a privilege.

Thank you – if you ever need anything, I love your magazine, and thank you for your encouragement and taking the time to talk to me!

Rebel Music: Bob Marley & Roots Reggae, the new book by Kate Simon, is now available to order from MarleyBook.com